Canonical Correlation Analysis¶

Can we quantify the associations between two sets of variables?

Do last year’s labor data relate or explain this year’s labor situation?

Are the math science performances of students related to their reading performances?

Are there associations between government policies and economic variables?

For decathlon athletes, is the track event performances correlated with the performance in field events?

Objective¶

Hotelling (1936) extended the idea of multiple correlation to the problem of measuring linear association between two groups of variables, say \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\). Thus we consider the simple correlation coefficient between every pair of linear combinations of elements of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and of \(\boldsymbol{y}\) and choose the maximum.

This maximum, \(\rho_1\), is called the first canonical correlation and the corresponding pair of linear combinations, say \((U_1, V_1)\), is called the first pair of canonical variables.

Since each group has more than one variable, one single correlation coefficient may miss significant linear association in other dimensions. So we consider the subclass of all pairs of linear combinations of elements of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\) whose members are uncorrelated with \((U_1, V_1)\). The maximum simple correlation coefficient, \(\rho _2\), of such pairs is called the second canonical correlation and the pair, say \((U_2, V_2)\), achieving this maximum is called the second pair of canonical variables.

Continuing this way we shall get the \(k\) canonical correlations and the corresponding pairs of canonical variables, where \(k=\min(d_x, d_y)\) is the smallest dimension of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\).

Alternative formulations include

minimizing the difference between two projected spaces, i.e. we want to predict projected \(\boldsymbol{y}\) by projected \(\boldsymbol{x}\).

\[\begin{split} \begin{equation} \begin{array}{ll} \min & \left\| \boldsymbol{X} \boldsymbol{V} - \boldsymbol{Y}\boldsymbol{W} \right\|_{F}^{2} \\ \text {s.t.} & \boldsymbol{V} ^\top \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{xx} \boldsymbol{V} = \boldsymbol{W} ^\top \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{y y} \boldsymbol{W} = \boldsymbol{I}_k \\ & \boldsymbol{V} \in \mathbb{R} ^{d_x \times k} \quad \boldsymbol{W} \in \mathbb{R} ^{d_y \times k} \\ \end{array} \end{equation} \end{split}\]maximizing the trace

\[\begin{split} \begin{equation} \begin{array}{ll} \max & \operatorname{tr} \left( \boldsymbol{V} ^\top \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{x y} \boldsymbol{W} \right) \\ \text {s.t.} & \boldsymbol{V} ^\top \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{x x} \boldsymbol{V} = \boldsymbol{W} ^\top \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{y y} \boldsymbol{W} = \boldsymbol{I}_k \\ & \boldsymbol{V} \in \mathbb{R} ^{d_x \times k} \quad \boldsymbol{W} \in \mathbb{R} ^{d_y \times k} \\ \end{array} \end{equation} \end{split}\]

Learning¶

Partition the covariance matrix of full rank in accordance with two groups of variables,

Sequential Optimization¶

The first canonical correlation, \(\rho _1\), equals the maximum correlation between all pairs of linear combinations of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\) with unit variance. That is,

If the maximum is achieved at \(\boldsymbol{v} _1\) and \(\boldsymbol{w} _1\), then the first pair of canonical variables are defined as

Successively, for \(i = 2, \ldots, k\), the \(i\)-th canonical correlation \(\rho_i\) is defined as

If the maximum is achieved at \(\boldsymbol{v} _i\) and \(\boldsymbol{w} _i\), then the first pair of canonical variables are defined as

The uncorrelated constraint, for example, when solving for the second pair \((U_2, V_2)\), are

Spectral Decomposition¶

Rather than obtaining pairs of canonical variables and canonical correlation sequentially, it can be shown that the canonical correlations \(\rho\)’s and hence pairs of canonical variables \((U,V)\)’s can be obtained simultaneously by solving for the eigenvalues \(\rho^2\)’s and eigenvectors \(\boldsymbol{v}\)’s from

A difficulty of this problem is that the matrix \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xy} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yx}\) is not symmetric. Consequently, the symmetric eigenproblem

is considered instead for the computational efficiency. Note that the two matrices possess the same eigenvalues and their eigenvectors are linearly related by \(\boldsymbol{v} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{{xx}}^{-1/2} \boldsymbol{u}\). Note that \(\boldsymbol{v}\) need to be normalized to satisfy the constraint \(\boldsymbol{v}^{\top} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{x x} \boldsymbol{v}=1\).

Then we can find \(\boldsymbol{w} \propto \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{y y}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{y x} \boldsymbol{v}\) subject to the constraint \(\boldsymbol{w}^{\top} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy} \boldsymbol{w}=1\).

Note that the maximal embedding dimension is \(\max(k) = \min(d_x, d_y)\).

Derivation

We consider the following maximization problem:

The Lagrangian is

The first order conditions are

Premultiply \((1)\) by \(\boldsymbol{v} ^\top\) and \((2)\) by \(\boldsymbol{w} ^\top\), we have

which implies that \(\lambda_x = \lambda_y\). Let \(\lambda_x = \lambda_y = \lambda\). Suppose \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{yy}\) is invertible, then \((2)\) gives

Substituting this into \((1)\) gives

i.e.,

Suppose \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{xx}\) is invertible, then it becomes an eigenproblem

Once the solution for \(\boldsymbol{v}\) is obtained, the solution for \(\boldsymbol{w}\) can be obtained by \((3)\)

with the normalized condition

To convert the eigenproblem to be symmetric for computational efficiency, we can write \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{xx} = (\boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{xx} ^{1/2}) (\boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{xx} ^{1/2})\) and let \(\boldsymbol{u} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{xx} ^{1/2} \boldsymbol{v}\) or \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{xx} ^{-1/2} \boldsymbol{u} = \boldsymbol{v}\). Substituting this into

gives

Then the eigenproblem becomes symmetric and easier to solve. We can find \(\boldsymbol{u}\) and then find \(\boldsymbol{v} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{xx} ^{-1/2} \boldsymbol{u}\), and then find \(\boldsymbol{w} \propto \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{y y}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{y x} \boldsymbol{v}\).

Properties¶

\(\operatorname{Var}\left(U_{k}\right) = \operatorname{Var}\left(V_{k}\right)=1\)

\(0 = \operatorname{Cov}\left(U_{k}, U_{\ell}\right) = \operatorname{Cov}\left(V_{k}, V_{\ell}\right)=\operatorname{Cov}\left(U_{k}, V_{\ell}\right) = \operatorname{Cov}\left(U_{\ell}, V_{k}\right)\text { for } k \neq \ell\)

\(\operatorname{Cov}\left(U_{i}, V_{i}\right)=\rho_{i}\), where \(\rho_i^2\) is the \(i\)-th largest eigenvalue of the following matrices

\(d_x \times d_x \quad \boldsymbol{C} \boldsymbol{C}^{\top}=\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xy} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yx} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1 / 2}\) where \(\boldsymbol{C} =\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xy} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{-1/2}\)

\(d_y \times d_y \quad \boldsymbol{C}^{\top} \boldsymbol{C}=\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yx} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xy} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{-1 / 2}\)

\(d_x \times d_x \quad \boldsymbol{A}=\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xy} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yx}=\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{C} \boldsymbol{C}^{\top} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{1 / 2}\)

\(d_y \times d_y \quad \boldsymbol{B}=\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yx} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xy}=\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{-1 / 2} \boldsymbol{C}^{\top} \boldsymbol{C} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{1 / 2}\)

In fact, they are similar \(\boldsymbol{A} \sim \boldsymbol{C} \boldsymbol{C} ^{\top}\), \(\boldsymbol{B} \sim \boldsymbol{C} ^{\top} \boldsymbol{C}\), and \(\boldsymbol{C} \boldsymbol{C} ^{\top}\) share the same nonzero eigenvalues with \(\boldsymbol{C} ^{\top} \boldsymbol{C}\) (hint: SVD).

The above identities can be summarized as

\[\begin{split} \operatorname{Cov}\left([U_{1}, \cdots, U_{k}, V_{1}, \cdots, V_{k}]\right)=\left[\begin{array}{cc} \boldsymbol{I}_{k} & \boldsymbol{R}_{k} \\ \boldsymbol{R}_{k} & \boldsymbol{I}_{k} \end{array}\right], \quad \boldsymbol{R}_{k}=\operatorname{diag}\left[\rho_{1}^{*}, \cdots, \rho_{k}^{*}\right] \end{split}\]If sort in canonical variate pairs,

\[\begin{split} \operatorname{Cov}\left([U_{1}, V_{1}, \cdots, U_{k}, V_{k}]\right)=\operatorname{diag}\left[\boldsymbol{D}_{1}, \cdots, \boldsymbol{D}_{k}\right], \quad \boldsymbol{D}_{i}=\left[\begin{array}{cc} 1 & \rho_{i}^{*} \\ \rho_{i}^{*} & 1 \end{array}\right] \end{split}\]Invariance property: Canonical correlations \(\rho_i\)’s between \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\) are the same as those between \(\boldsymbol{A} _1 \boldsymbol{x} + \boldsymbol{c}_1\) and \(\boldsymbol{A} _2 \boldsymbol{y} + \boldsymbol{c} _2\), where both \(\boldsymbol{A} _1\) and \(\boldsymbol{A} _2\) are non-singular square matrices and their computation can be based on either the partitioned covariance matrix or the partitioned correlation matrix. However, the canonical coefficients contained in \(\boldsymbol{v} _k\) and \(\boldsymbol{w} _k\) are not invariant under the same transform, nor their estimates.

Model Selection¶

Given a sample of data matrix \(\boldsymbol{X}\) and \(\boldsymbol{Y}\), let \(\boldsymbol{S} _{xx}, \boldsymbol{S} _{12}, \boldsymbol{S} _{yy}\) and \(\boldsymbol{S} _{yx}\) be the corresponding sub-matrices of the sample covariance matrix \(\boldsymbol{S}\). For \(i = 1, 2, \ldots, k\), let \(r_i ^2, \boldsymbol{a} _i\) and \(\boldsymbol{b} _i\) be respectively the sample estimators of \(\rho_i^2, \boldsymbol{v} _i\) and \(\boldsymbol{w} _i\), all based on

in parallel to \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1/2} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xy} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yy}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{yx} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}_{xx}^{-1/2}\). Then the \(i\)-th pair of sample canonical variables \(\widehat{U}_i, \widehat{V}_i\) is

How to choose \(k\)?

Hypothesis Testing¶

Since these are not the population quantities and we don’t know whether some \(\rho_i\) are zero, or equivalently how many pairs of the canonical variables based on the sample to be retained. This can be answered by testing a sequence of null hypotheses of the form

until we accept one of them. Note that the first hypothesis of retaining no pair,

is equivalent to independence between \(\boldsymbol{x} 1\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\), or \(H_0: \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _{12} = 0\). \boldsymbol{I}f it is rejected, test

i.e., retain only the first pair; if rejected, test

i.e., retain only the first two pairs, etc., until we obtain \(k\) such that

is accepted. Then we shall retain only the first \(k\) pairs of canonical variables to describe the linear association between \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\).

Interpretation¶

The meanings of the canonical variables are to be interpreted either

in terms of the relative weighting of the coefficients associated with the original variables, or

by comparison of the correlations of a canonical variable with original variables.

It is an art to provide a good name to a canonical variable that represents the interpretation and often requires subject-matter knowledge in the field.

Pros and Cons¶

Discriminative Power¶

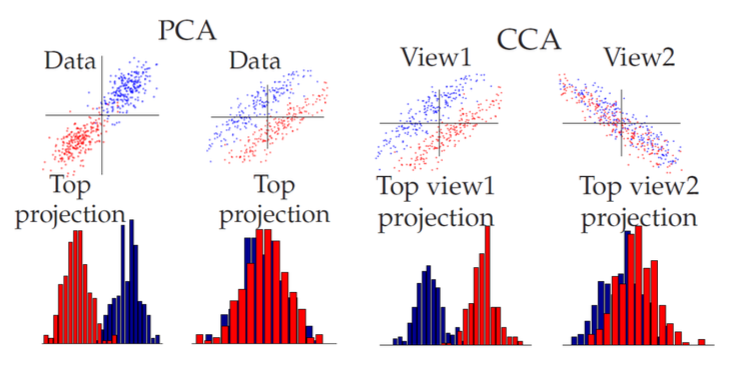

Unlike PCA, CCA has discriminative power in some cases. \boldsymbol{I}n the comparison below, in the first scatter-plot, the principal direction is the discriminative direction, while in the second plot it is not. The 3rd (same as the 2nd) and the 4th plots corresponds to \(\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathbb{R} ^2\) and \(\boldsymbol{y} \in \mathbb{R} ^2\). The two colors means two kinds of data points in the \(n\times 4\) data set, but the color labels are shown to CCA. The CCA solutions to \(\boldsymbol{x}\) (3rd plot) is the direction \((-1,1)\) and to \(\boldsymbol{y}\) (4th plot) is the direction \((-1,-1)\). Because they are the highest correlation pair of directions.

Fig. 101 CCA has discriminative power [Livescu 2021]¶

Overfitting¶

CCA tends to overfit, i.e. find spurious correlations in the training data. Solutions:

regularize CCA

do an initial dimensionality reduction via PCA to filter the tiny signals that are correlated.

Regularized CCA¶

To regularize CCA, we can add small constant \(r\) (noise) to the covariance matrices of \(\boldsymbol{x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y}\).

Then we solve for the eigenvalues’s and eigenvectors’s of the new matrix

Kernel CCA¶

Like Kernel PCA, we can generalize CCA with kernels.

Ref

A kernel method for canonical correlation analysis. Shotaro Akaho 2001.

Canonical correlation analysis; An overview with application to learning methods. David R. Hardoon 2003.

Kernelization¶

Recall the original optimization problem of CCA

Consider two feature transformations, \(\boldsymbol{\phi} _x: \mathbb{R} ^{d_x} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} ^{p_x}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\phi} _x: \mathbb{R} ^{d_y} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} ^{p_y}\). Let

\(\boldsymbol{\Phi} _x\) and \(\boldsymbol{\Phi} _y\) be the transformed data matrix.

\(\boldsymbol{C}_x = \frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{\Phi} _x ^\top \boldsymbol{\Phi} _x, \boldsymbol{C}_y = \frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{\Phi} _y ^\top \boldsymbol{\Phi} _y, \boldsymbol{C}_{xy} = \frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{\Phi} _x ^\top \boldsymbol{\Phi} _y, \boldsymbol{C}_{yx} = \frac{1}{n} \boldsymbol{\Phi} _y ^\top \boldsymbol{\Phi} _x\) be the corresponding variance-covariance matrices.

Then the problem is to solve \(\boldsymbol{v}, \boldsymbol{w}\) in

It can be shown that, the solution vectors \(\boldsymbol{v}\) and \(\boldsymbol{w}\) are linear combinations of the data vectors \(\boldsymbol{\phi} _x(\boldsymbol{x} _i)\) and \(\boldsymbol{\phi} _y (\boldsymbol{y} _i)\), i.e.

Derivation??

Substituting them back to the objective function, we have

which is the dual form.

Note that the value if not affected by re-scaling of \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) either together or independently. Hence the KCCA optimization problem is equivalent to

The corresponding Lagrangian is

Taking derivatives w.r.t. \(\boldsymbol{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\) gives

Subtracting \(\boldsymbol{\boldsymbol{\beta}} ^\top\) times the second equation from \(\boldsymbol{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} ^\top\) times the first we have

which together with the constraints implies \(\lambda_\alpha - \lambda_\beta =0\). Let them be \(\lambda\). Suppose \(\boldsymbol{\boldsymbol{K}} _x\) and \(\boldsymbol{\boldsymbol{K}} _y\) are invertible (usually the case), then the system of equations given by the derivatives yields

and hence

or

Therefore, \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) can be any unit vector \(\boldsymbol{e} _j\), and we can find the corresponding \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) be the \(j\)-th column of \(\boldsymbol{K}_{y}^{-1} \boldsymbol{K}_{x}\). Substituting back to the objective function, we found \(\rho = 1\). The corresponding weights are \(\boldsymbol{v} = \boldsymbol{\Phi} _x ^\top \boldsymbol{\alpha} = \boldsymbol{\phi} (\boldsymbol{x} _j)\), and \(\boldsymbol{w} = \boldsymbol{\Phi} _y ^\top \boldsymbol{\beta}\).

This is a trivial solution. It is therefore clear that a naive application of CCA in kernel defined feature space will not provide useful results. Regularization is necessary.

Regularization¶

To obtain non-trivial solution, we add regularization term, which is typically the norm of the weights \(\boldsymbol{v}\) and \(\boldsymbol{w}\).

Likewise, we observe that the new regularized equation is not affected by re-scaling of \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) or \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\), hence the optimization problem is subject to

The resulting Lagrangian is

The derivatives are

By the same trick, we have

which gives \(\lambda_\alpha = \lambda_\beta =0\). Let them be \(\lambda\), and suppose \(\boldsymbol{K}_x\) and \(\boldsymbol{K}_y\) are invertible, we have

and hence

Therefore, we just solve the above eigenproblem to get meaningful \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\), and then compute \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\).

Learning¶

From the analysis above, the steps to train a kernel CCA are

Choose a kernel function \(k(\cdot, \cdot)\).

Compute the centered kernel matrix \(\boldsymbol{K} ^c _x = (\boldsymbol{I} - \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{u} ^\top )\boldsymbol{K}_x(\boldsymbol{I} - \boldsymbol{u} \boldsymbol{u} ^\top)\) and \(\boldsymbol{K} _y ^c\)

Find the first \(k\) eigenvectors of \(\left(\boldsymbol{K} ^c_{x}+r \boldsymbol{I}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{K} ^\prime_{y}\left(\boldsymbol{K} ^c_{y}+r \boldsymbol{I}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{K} ^c_{x}\), store in \(\boldsymbol{A}\).

Then

to project a new data vector \(\boldsymbol{x}\), note that

\[ \boldsymbol{w} _ {x,j} = \boldsymbol{\Phi} _x ^\top \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{j} \]Hence, the embeddings \(\boldsymbol{z}\) of a vector \(\boldsymbol{x}\) is

\[\begin{split} \boldsymbol{z} _x = \left[\begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol{w} _{x, 1} ^\top \boldsymbol{\phi}(\boldsymbol{x}) \\ \boldsymbol{w} _{x, 2} ^\top \boldsymbol{\phi}(\boldsymbol{x}) \\ \vdots \\ \boldsymbol{w} _{x, k} ^\top \boldsymbol{\phi}(\boldsymbol{x}) \\ \end{array}\right] = \left[\begin{array}{c} \boldsymbol{\alpha} _1 ^\top \boldsymbol{\Phi}_x \\ \boldsymbol{\alpha} _2 ^\top \boldsymbol{\Phi}_x \\ \vdots \\ \boldsymbol{\alpha} _k ^\top \boldsymbol{\Phi}_x \\ \end{array}\right] \boldsymbol{\phi}(\boldsymbol{x}) = \boldsymbol{A} ^\top \boldsymbol{\Phi}_x \boldsymbol{\phi}(\boldsymbol{x}) = \boldsymbol{A} ^\top \left[\begin{array}{c} k(\boldsymbol{x} _1, \boldsymbol{x}) \\ k(\boldsymbol{x} _2, \boldsymbol{x}) \\ \vdots \\ k(\boldsymbol{x} _n, \boldsymbol{x}) \\ \end{array}\right]\\ \end{split}\]where \(\boldsymbol{A} _{n\times k}\) are the first \(k\) eigenvectors \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\).

to project the training data \(\boldsymbol{X}\),

\[\boldsymbol{Z} ^\top = \boldsymbol{A} ^\top \boldsymbol{K}_x \text{ or } \boldsymbol{Z} = \boldsymbol{K}_x \boldsymbol{A} \]to project a new data matrix \(\boldsymbol{X} ^\prime _{m \times d}\),

\[\begin{split} \boldsymbol{Z} _{x ^\prime} ^\top = \boldsymbol{A} ^\top \left[\begin{array}{ccc} k(\boldsymbol{x} _1, \boldsymbol{x ^\prime_1}) & \ldots &k(\boldsymbol{x} _1, \boldsymbol{x ^\prime_m}) \\ k(\boldsymbol{x} _2, \boldsymbol{x ^\prime_1}) & \ldots &k(\boldsymbol{x} _2, \boldsymbol{x ^\prime_m}) \\ \vdots &&\vdots \\ k(\boldsymbol{x} _n, \boldsymbol{x ^\prime_1}) & \ldots &k(\boldsymbol{x} _n, \boldsymbol{x ^\prime_m}) \\ \end{array}\right]\\ \end{split}\]

Model Selection¶

Hyperparameters/settings include number of components \(k\), choice of kernel, and the regularization coefficient \(r\).