Common Tests¶

Theories¶

We first introduce some theories for statistical inference.

Sample Statistics¶

For a random sample \((X_1, \ldots, X_n)\), the sample mean and sample variance can be computed as

They are unbiased estimators since

where we used the fact that \(\mathbb{E} [\bar{X}^2] = \operatorname{Var}\left( \bar{X} \right) + \mathbb{E} [\bar{X}] ^2 = \frac{1}{n} \sigma^2 + \mu^2\).

If the random variables are i.i.d. sampled from normal distribution \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N}\), then \(\bar{X}\) and \(S^2\) (both are random) are independent.

Distribution Derived from Normal¶

Standard Normal Distributions¶

If \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma^2)\), then

Proof

Since \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim}\mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma)\), then \(Z_i = \frac{ X_i - \mu}{ \sigma} \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (0, 1)\)

Chi-squared Distributions¶

If \(Z_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (0, 1)\), then their squared sum follows Chi-squared distribution with degree of freedom \(n\), mean \(n\), and variance \(2n\).

If \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma^2)\), then we can find a distribution for the sample variance \(S^2\) as

which does not depends on the true mean \(\mu\).

\(t\) Distributions¶

If \(Z \sim \mathcal{N} (0, 1)\), and \(V \sim \chi ^2 _n\) and \(Z\) and \(V\) are independent, then

In short, an independent standard normal random variable and a chi-squared random variable can be used to construct a \(t\) distribution. We will use this lemma in a moment.

If \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma^2)\), then

Proof

Rewritting the LHS gives

For the numerator we have shown that \(Y=\sqrt{n} \frac{\bar{X} - \mu}{\sigma} \sim \mathcal{N} (0, 1)\). For the ratio in the denominator \(V = \frac{(n-1)S^2}{\sigma^2} \sim \chi ^2 _{n-1}\) by the theorem above. Also note that \(Y\) and \(V\) are independent since \(\bar{X}\) and \(S^2\) are independent. By the theorem above, the \(\frac{Y}{\sqrt{V/(n-1)}}\) follows a \(t\) distribution with d.f. \(n-1\).

Confidence Intervals¶

Given a sample \((X_1, \ldots, X_n)\), we want to find two bounds \(\hat{\theta}_L\) and \(\hat{\theta}_R\) for the unknown parameter \(\theta\), such that \(\mathbb{P} (\hat{\theta}_L <\theta < \hat{\theta}_R) = 1- \alpha\). The interval \((\hat{\theta}_L, \hat{\theta}_R)\) is called the \((1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval.

We first give a summary table and then introduce the details.

Scenario |

Distribution |

C.I |

|---|---|---|

Normal Means (known \(\sigma\)) |

\(\frac{\bar{X} - \mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}} \sim \mathcal{N} (0, 1)\) |

\(\bar{X} \pm z_{\alpha/2} \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\) |

Normal Means (unknown \(\sigma\)) |

\(\frac{\bar{X} - \mu}{S/\sqrt{n}} \sim t_{n-1}\) |

\(\bar{X} \pm t_{\alpha/2} \frac{S}{\sqrt{n}}\) |

Normal Variance |

\(\frac{(n-1)S^2}{\sigma^2 } \sim \chi ^2 _{n-1}\) |

\(\left(\frac{(n-1) S^{2}}{\chi_{R, n-1}^{2}}, \frac{(n-1) S^{2}}{\chi_{L, n-1}^{2}}\right)\) |

General Means (\(n \ge 30\)) |

\(\frac{\left(\bar{X}-\mu\right)}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}}\overset{\mathcal{D}}{\rightarrow} \mathcal{N}(0,1)\) |

\(\bar{X} \pm z_{\alpha/2} \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\) (*) |

\(*\) Approximate. Replace \(\sigma\) by \(S\) if \(\sigma\) is unknown.

CI for Normal Means¶

Known Variance¶

Suppose the observations are from a normal distribution, \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma^2)\) where \(\sigma^2\) is known. We have shown that

Hence, from the standard normal distribution, we can find the cutoff \(z_{\alpha/2}\) such that

Substituting \(Z = \frac{\bar{X} - \mu}{\sigma/\sqrt{n}}\) gives the confidence interval for \(\mu\).

Sometimes people just write \(\bar{X} \pm z_{\alpha/2} \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\).

Unknwon Variance¶

Suppose the observations are from a normal distribution, \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma^2)\) where \(\sigma^2\) is unknown. We have shown that

Hence, from the \(t_{n-1}\) distribution, we can find a cutoff \(t_{\alpha/2}\) such that

Substituting \(T = \frac{\bar{X} - \mu}{S/\sqrt{n}}\) gives the confidence interval for \(\mu\).

Sometimes people just write \(\bar{X} \pm t_{\alpha/2} \frac{S}{\sqrt{n}}\).

Why “Confidence”?

Note that the confidence interval \(\left( \bar{X} - t_{\alpha/2} \frac{S}{\sqrt{n}}, \bar{X} + t_{\alpha/2} \frac{S}{\sqrt{n}} \right)\) is a random interval; its center \(\bar{X}\) and its width \(t_{\alpha/2} \frac{S}{\sqrt{n}}\) both depend on the data. After generating the data and calculating \(\bar{X}\) and \(S^2\), this gives us a specific interval. It is no longer accurate to say that \(\mathbb{P} (\mu \in \text{interval} ) = 1-\alpha\); the statement is either TRUE or FALSE (i.e. the event \(\left\{ \mu \in \text{interval} \right\}\) has already either occurred or not).

However, we cannot see whether it’s true or false as we don’t know \(\mu\). Since before drawing the data we had a \(1-\alpha\) probability of construting an interval for which the statement is true, we now say that we have \(1-\alpha\) confidence that the statement is true. This is a confidence interval for \(\mu\).

CI for Normal Variances¶

Suppose the observations are from a normal distribution, \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma^2)\) where \(\sigma^2\) is unknown. We have shown that

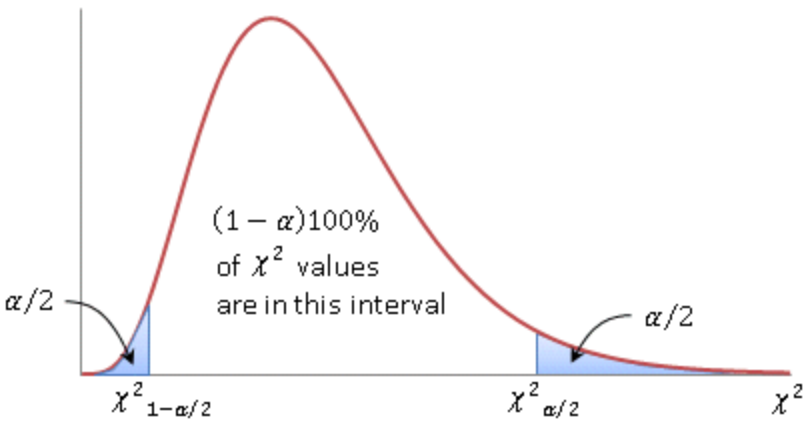

Let \(\chi ^2 _{L, n-1}\) and \(\chi ^2 _{R, n-1}\) be positive number such that

Then replacing \(W\) by \(\frac{(n-1)S^2}{\sigma^2 }\) in the above we obtain

Therefore

is a \(1-\alpha\) confidence interval for \(\sigma^2\).

Note that the \(\chi ^2\) distribution is not symmetric. A common way to choose \(\chi ^2 _{L, n-1}\) and \(\chi ^2 _{R, n-1}\) is such that the two tail probabilities are both \(\alpha/2\), as shown below.

A less common way is to find a horizontal line such that the two resulting tail probabilities sum up to \(\alpha\).

CI for General Means¶

The Central Limit Theorem says the normalized sample mean converge in distribution to a standard normal random variable,

Hence, we have, approximately,

Rearranging the terms gives

Therefore,

is, approximately, a \(1-\alpha\) confidence interval for \(\mu\). The approximation is good if sample size \(n > 30\)

If \(\sigma\) is unknonw, then replace it by \(S\).

One-sample Mean Tests¶

The most common test is to test the mean of a given sample of observations.

The null hypothesis is \(H_0: \mu = \mu_0\). The alterntive hypothesis is \(H_1: \mu \ne \mu_0\) for a two-sided test, or \(H_1: \mu < \mu_0\) or \(H_1: \mu > \mu_0\) for one-sided tests.

Normal Means¶

Known Variance¶

Suppose the observations are from a normal distribution, \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma^2)\) where \(\sigma^2\) is known. We have shown that

Hence, a test statistic can be

which follows a standard normal distribution under \(H_0\). The rejection region (RR) depends on the alternative hypoehtsis.

\(H_1\) |

RR |

RR if \(\alpha = 0.05\) |

|---|---|---|

\(\mu < \mu_0\) |

\(Z < - z_\alpha\) |

\(Z < - 1.645\) |

\(\mu > \mu_0\) |

\(Z > z_\alpha\) |

\(Z > 1.645\) |

\(\mu \ne \mu_0\) |

\(\left\vert Z \right\vert > z_{\alpha/2}\) |

\(\left\vert Z \right\vert > 1.960\) |

This is often known as a \(Z\)-test. But in practice, the population variance \(\sigma^2\) is unknown.

Unknown Variance¶

When \(X_i \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \mathcal{N} (\mu, \sigma^2)\) where \(\sigma^2\) is unknown, we have shown that

Hence, a test statistic can be

which follows a \(t_{n-1}\) distribution under \(H_0\). The rejection region (RR) depends on the alternative hypoehtsis.

\(H_1\) |

RR |

|---|---|

\(\mu < \mu_0\) |

\(T < - t_{n-1}^{\alpha}\) |

\(\mu > \mu_0\) |

\(T > t_{n-1}^{\alpha}\) |

\(\mu \ne \mu_0\) |

\(\left\vert T \right\vert > t_{n-1}^{\alpha/2}\) |

This is often known as a \(t\)-test.

General Means¶

By CLT, in for any distribution of \(X_i\), when the sample is large \((n \ge 30)\), we have

Hence a test statistic is

which approximately follows standard normal distribution. Then we use the usual \(Z\) test to decide the rejection regions.

For instance, if the null hypothesis is about a proportion \(H_0: p = p_0\), then we can model the random (binary) variable by a Bernoulli distribution \(X_i \sim \mathrm{Ber}(p_0)\) with mean \(p_0\) and variance \(p_0 (1-p_0)\). Therefore, the test statistic is

where \(\hat{p}\) is the observed proportion. A ususal \(Z\) test follows.

\(p\)-value Approach¶

Sometimes we can use the fundamental definition of \(p\)-value to compute it. Recall the definition is the probability of obtaining test results at least as extreme as the results actually observed, under the assumption that the null hypothesis is correct.

Binomial Distribution¶

We flip the coin 10 times and let \(X\) be the number of heads. Suppose we total number of heads \(X_{1}+\cdots+X_{10}=7\). Can we find the \(p\)-value for a test with rejection region of the form \(\{x \geq k\}\)

The observed value of the test statistic is \(\bar{X}=0.7\).

Since under the null hypothesis \(X=X_{1}+\cdots+X_{10} \sim \operatorname{Binomial}(10,0.5)\). Note the alternative hypothesis here is \(H_1: p > 0.5\).

For a two-sided test where \(H_1: p \ne 0.5\), the \(p\)-value is computed as

since ‘7 or more heads’ are as extreme as ‘3 or less heads’ under \(H_0\).

Geometric Distribution¶

Given \(X \sim \mathrm{Geo}(p)\), we can conduct a one-sided test

Let the observed value be \(k\). The \(p\)-value can be computed as

We then compare it with the significance level \(\alpha\) and draw a conclusion.

Alternatively, we can find a critical region by finding the integer \(j\) such that

If \(k \ge j\) then we reject \(H_0\). The actual significance level used here is \(\mathbb{P}(X \ge j \mid p=p_0)\).

Two-sample Mean Tests¶

Suppose we have two samples of data \(\left\{x_{1}, \cdots, x_{n}\right\}\) and \(\left\{y_{1}, \cdots, y_{m}\right\}\).

A question of interest: Did the two samples come from the same distribution, as opposed to, one sample having larger values than the other on average?

To model them, we assume

\(X_{i}, \cdots, X_{n}\) i.i.d. sampled from a distribution with mean with mean \(\mu_X\) and variance \(\sigma^2 _X\)

\(Y_{i}, \cdots, Y_{m}\) i.i.d. sampled from a distribution with mean with mean \(\mu_Y\) and variance \(\sigma^2 _Y\)

We are interested in comparing the two samples, often by comparing the two means \(\mu_X\) and \(\mu_Y\).

An unbiased estimator for the difference in mean \(\mu_X - \mu_Y\) is \(\bar{X} - \bar{Y}\). To provide standard error to this estimator, \(\operatorname{Var}\left( \bar{X} - \bar{Y} \right)\) need to be estimated, contingent on sample properties.

Paired¶

In many studies, the \(i\)-th measurements in the two samples \(x_i\) and \(y_i\) actually are related, such as measurements before and after a treatment from the same subject.

When \(m = n\) and \(\operatorname{Corr}\left( X_i,Y_i \right) = \rho \ne 0\), very often \(\rho >0\). Then,

To have a more precise variance estimate, it is appropriate to consider pairing \(X_i\) and \(Y_i\) by investigating their difference:

Note that \(D_i\)’s are i.i.d. under the i.i.d. assumption of each of the two samples, with

Then essentially, we changed the inference problem into that of a one-sample case.

An unbiased estimator for the variance of difference \(\sigma^2_D\) is the sample variance.

Normal¶

If \(X \sim \mathcal{N} \left(\mu_{X}, \sigma_{X}^{2}\right), Y \sim \mathcal{N} \left(\mu_{Y}, \sigma_{Y}^{2}\right)\), then we have the distributions for the sample estimators

In addition, they are independent. By the definition of \(t\)-distribution, the test statistic

is a pivot quantity not depending on the parameters if we are testing a hypothesis on \(\mu_D\). For instance,

A \((1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for the true difference in mean \(\mu_X - \mu_Y\) is

Non-normal¶

When the samples are not normally distributed, \(t_{n-1}\) can be used as an approximate distribution.

When n is large, we may use the Central Limit Theorem,

The asymptotic pivotal property can be used to conduct hypothesis tests.

A \((1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for the true difference in mean \(\mu_X - \mu_Y\) is

Independent¶

Now we consider \(X_i\) and \(Y_j\) are independent.

Equal Variance¶

If \(\sigma^2 _X = \sigma^2 _Y\), then

and both sample variances \(S_X^2\) and \(S_Y^2\) are unbiased estimators of \(\sigma^2\)

A better unbiased estimator is the pooled sample variance

which has a larger testing power than the two sample variances.

Normal¶

If both \(X\) and \(Y\) are of normal distributions, then the test statistic is

A \((1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for the true difference in mean \(\mu_X - \mu_Y\) is

Non-normal¶

When the samples are not normally distributed, \(t_{n+m-2}\) distribution can be used as an approximation.

When both \(n\) and \(m\) are large, we may apply the Central Limit Theorem,

Pooling vs paring

Consider the case n = m with equal variance.

Under assumption that the two samples are independent, the variance is

\[ \operatorname{Var}(\bar{X}-\bar{Y})= \frac{2 \sigma^{2}}{n} \]The pooled sample variance is the appropriate estimator to be used.

If the two samples were correlated with \(Corr(X_i, X_j) = \rho > 0\), the variance becomes smaller

\[ \operatorname{Var} (\bar{X}-\bar{Y})=(1-\rho) \frac{2 \sigma^{2}}{n}< \frac{2 \sigma^{2}}{n} \]

As a result, when correlation exists, the smaller paired sample variance is the appropriate one to use, since the test statistic using it has a larger power.

On the other hand, if the correlation is substantial and we fail to take it into consideration, the pooled sample variance estimator likely will overestimate the variance, and the estimate could be too large to be useful.

Unequal Variance¶

If \(\sigma_{X}^{2} \neq \sigma_{Y}^{2}\), the variance we are interested to estimate has the form

which can be estimated by the unbiased estimator

It is complicated to construct a pivot quantity like we did for the previous cases. Consider

When both \(X\) and \(Y\) are of normal distributions, we have

But since \(\sigma_{X}^{2} \neq \sigma_{Y}^{2}\), the summation

is not a multiple of a \(\chi^2\) distribution.

Hence, \(T\) is not \(t\)-distributed.

If \(n\) and \(m\) are both large, we can resort to Central Limit Theorem as usual,

The asymptotic approximation lead to a \((1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for the true difference in mean \(\mu_X - \mu_Y\)

However, there is a better approximation using \(t_v\) distribution than the normal approximation.

But the degree of freedom \(v\) is involved. It is estimated by Welch-Satterthwaite approximation,

The asymptotic approximation lead to a \((1-\alpha)\%\) confidence interval for the true difference in mean \(\mu_X - \mu_Y\),

Summary¶

The analysis for the above cases are summarized into the table below. In general, if \(X\) and \(Y\) are of normal distributions, the pivot quantity follows a known distribution. If not, we use CLT to obtain an approximate distribution, which requires large \(n\) and \(m\).

Dependency |

Test statistic |

Normal |

Non-normal, large \(n, m\) |

|---|---|---|---|

Paired (reduced to a univariate test) |

\(\frac{\bar{D}-\mu_{D}}{S_{D} / \sqrt{n}}\) |

\(\sim t_{n-1}\) |

\(\stackrel{\mathcal{D}}{\longrightarrow} \mathcal{N}(0,1)\) |

Independent with equal variance |

\(\frac{(\bar{X}-\bar{Y})-\left(\mu_{X}-\mu_{Y}\right)}{S_{p} \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}+\frac{1}{m}}}\) |

\(\sim t_{n+m-2}\) |

\(\stackrel{\mathcal{D}}{\longrightarrow} \mathcal{N}(0,1)\) |

Independent with unequal variance |

\(\frac{\left( \bar{X}-\bar{Y} \right)-\left(\mu_{X}-\mu_{Y}\right)}{\sqrt{\frac{S_{X}^{2}}{n}+\frac{S_{Y}^{2}}{m}}}\) |

/ |

\(\stackrel{\mathcal{D}}{\longrightarrow} t_v\) |

Multi-sample Mean Tests¶

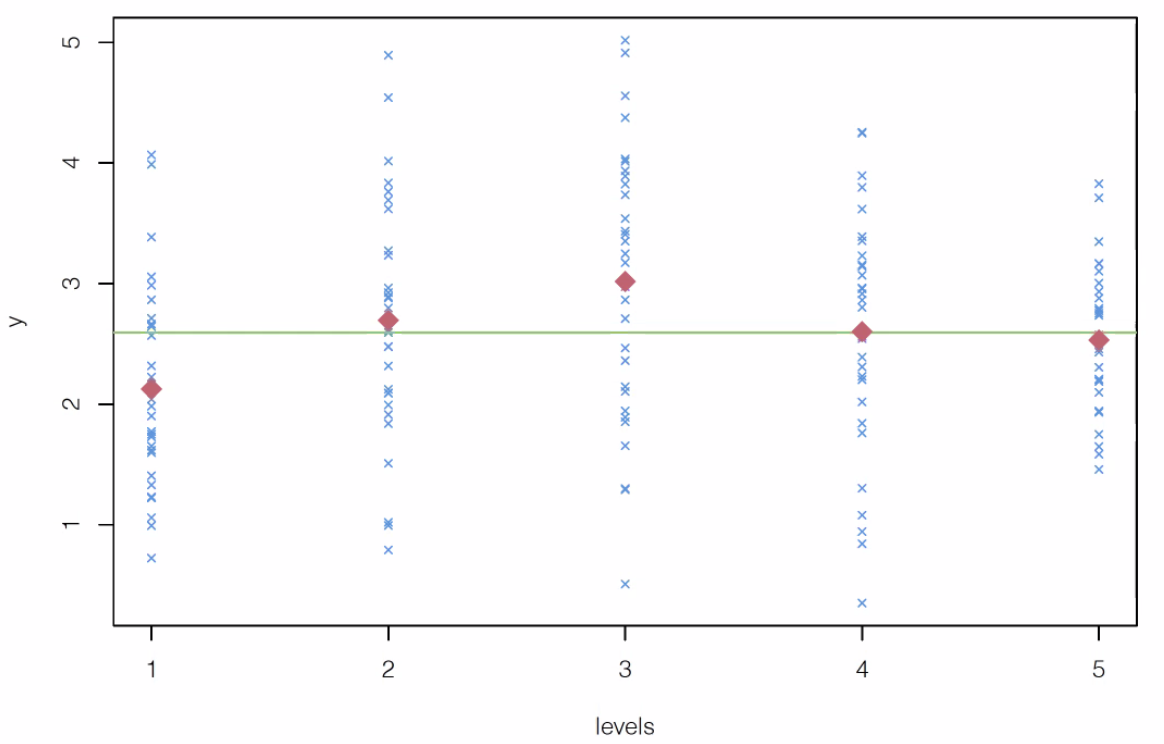

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is used to compare several univariate sample means. For instance, in the plot below, we have five levels and observed the response \(y\). We are interested in whether the five means are equal.

Fig. 27 One-way Layout¶

Model¶

There are \(n_\ell\) observations from population or treatment group \(\ell = 1, 2, \ldots, g\)

where

\(\mu\) is the overall mean parameter.

\(\tau_{\ell}\) is the treatment effect parameter of the \(\ell\) th population or \(\ell\) th treatment group.

\(e_{\ell j} \sim N\left(0, \sigma^{2}\right)\) is individual specific homogenous noise.

Parameter constraint: We have one \(\mu\) and \(g\) number of \(\tau_\ell\), in total \(1 + g\) parameters. There should be a constraint on the parameters such as \(\sum_{\ell=1}^{g} n_{\ell} \tau_{\ell}=0\), to avoid redundancy or unidentifiability.

To detect differences in treatment effects among the groups, the first test of interest is

Equivalently, the model can be parameterized as \(X_{\ell j} = \mu_\ell + e_{\ell j}\) without any parameter constraint, and the null hypothesis of equal treatment effects becomes equal means \(H_0: \mu_1 = \ldots = \mu_g\).

Test Statistic¶

First, we decompose the observations as

where \(\bar{x}\) is the overall mean, \(\bar{x}_\ell\) is the \(\ell\)-th group mean. Hence, the observation can be seen as estimated overall mean + estimated treatment effect + estimated noise. Equivalently,

Summing up all squared terms, noticing that \(\sum_{\ell=1}^{g} \sum_{j=1}^{n_{\ell}}\left(\bar{x}_{\ell}-\bar{x}\right)\left(x_{\ell j}-\bar{x}_{\ell}\right)=0\), we have

The decomposition can be stated as

The corresponding numbers of independent quantities of each term, i.e. the degrees of freedom, have the relation

Therefore, we obtain the analysis of variance table

At test level \(\alpha\), the null \(H_0: \tau_{1}=\cdots=\tau_{g}=0\) is rejected if

Cavests in using anova()

In anova() function in R, if the group variable \(\ell\) is in numerical value, it is necessary to coerce it as data type factor by calling as.factor().

When \(g=2\), the ANOVA \(F\)-test reduces to the two-sample means \(t\)-test.

The null hypothesis is equal means \(H_0: \mu_1 = \mu_2\)

The test statistic have the relation \(t^2 = F\).

The two \(p\)-values are the same.

Multivariate Settings¶

Hotelling’s \(T^2\) Distribution¶

- Definition (Hotelling’s \(T^2\) Distribution )

Suppose random zero-mean Gaussian \(\boldsymbol{x} \sim \mathcal{N} _p(\boldsymbol{0} , \boldsymbol{\Sigma} )\) and Wishart random matrix \(\boldsymbol{V} \sim W_p(k, \boldsymbol{\Sigma} )\) are independent. Define

\[ T^2 = k \boldsymbol{x} ^{\top} \boldsymbol{V} ^{-1} \boldsymbol{x} \]Then \(T^2\) is said to follow a Hotelling’s \(T^2\) distribution with parameter \(p\) and \(k\), denoted as \(T^2(p, k)\).

In univariate sense, the Hotelling’s \(T^2\) statistic can be reduced to the squared \(t\)-statistic. Hence it can be seen as multivariate generalization of (squared) \(t\)-distribution.

- Properties

If \(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}\) and \(\boldsymbol{S}\) are respectively the sample mean vector and sample covariance matrix of a random sample of size \(n\) taken from \(\mathcal{N} _p(\boldsymbol{\mu} , \boldsymbol{\Sigma} )\), then

\[n(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}-\boldsymbol{\mu})^{\top} \boldsymbol{S}^{-1}(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}-\boldsymbol{\mu}) \sim T^{2}(p, n-1)\]The distribution of the quadratic form under non-normality is reasonably robust as long as the underlying multivariate distribution has pdf contours close to elliptical shape, but \(T^2\) is sensitive to the departure from such elliptical symmetry of the distribution.

Invariant under transformation of \(\boldsymbol{x}\):\(\boldsymbol{C} \boldsymbol{x} + \boldsymbol{d}\), where \(\boldsymbol{C}\) is non-singular.

Related to other distribution:

\(T^{2}(p, k)=\frac{k p}{k-p+1} F(p, k-p+1)\), usually used to find quantile \(T^2(\alpha)\).

\(T^{2}(1, k)=t^{2}(k)=F(1, k)\)

\(T^{2}(p, \infty) \rightarrow \chi ^2 _p\) by multivariate CLT, without assuming normality of the distribution of \(\boldsymbol{x}\)

Related to Mahalanobis distance: \(T^{2}=n D_{\boldsymbol{S}}^{2}(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}, \boldsymbol{\mu})\)

One-sample Mean¶

Assume \(\boldsymbol{x} \sim \mathcal{N} _p(\boldsymbol{0} , \boldsymbol{\Sigma} )\), want to test

- Test statistic under \(H_0\)

\(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\) is known:

\[T^{2}=n\left(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}-\boldsymbol{\mu}_{0}\right)^{\top} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}^{-1}\left(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}-\boldsymbol{\mu}_{0}\right) \sim \chi^{2}(p)\]\(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\) is unknown, estimated by \(\boldsymbol{S}\):

\[\begin{split}\begin{aligned} T^{2}=n\left(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}-\boldsymbol{\mu}_{0}\right)^{\top} \boldsymbol{S}^{-1}\left(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}-\boldsymbol{\mu}_{0}\right) &\sim T^{2}(p, n-1) \\ &\sim \frac{(n-1) p}{n-p} F(p, n-p) \\ & \rightarrow \chi ^2 _p \quad \text{as } n \rightarrow \infty \end{aligned}\end{split}\]Analogously, in univariate case,

\[\begin{split} \left\{\begin{array}{l} \frac{\sqrt{n}\left(\bar{x}-\mu_{0}\right)}{\sigma} \sim N(0,1) \text { if } \sigma^{2} \text { is known } \\ \frac{\sqrt{n}\left(\bar{x}-\mu_{0}\right)}{s} \sim t(n-1) \text { if } \sigma^{2} \text { is unknown. } \end{array}\right. \end{split}\]

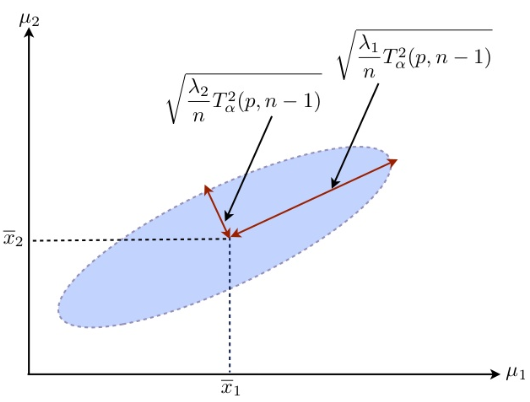

- Confidence Region

A \((1-\alpha)100\%\) confidence region for \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) is a \(p\)-dimensional ellipsoid centered at \(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}\), i.e. a collection of all those \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) which will not be rejected by the above \(T^2\) test at significance level \(\alpha\).

\[ \left\{\boldsymbol{\mu}: n(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}-\boldsymbol{\mu})^{\top} \boldsymbol{S}^{-1}(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}-\boldsymbol{\mu}) \leq T_{\alpha}^{2}(p, n-1)=c_{\alpha}\right\} \]

Fig. 28 Confidence region¶

This confidence ellipsoid above is the most precise confidence region of the vector \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\), in the sense that any other form of confidence region for \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) with the same confidence level \((1-\alpha)\) will have larger volume in the \(p\)-dimensional space of \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) and hence less precise.

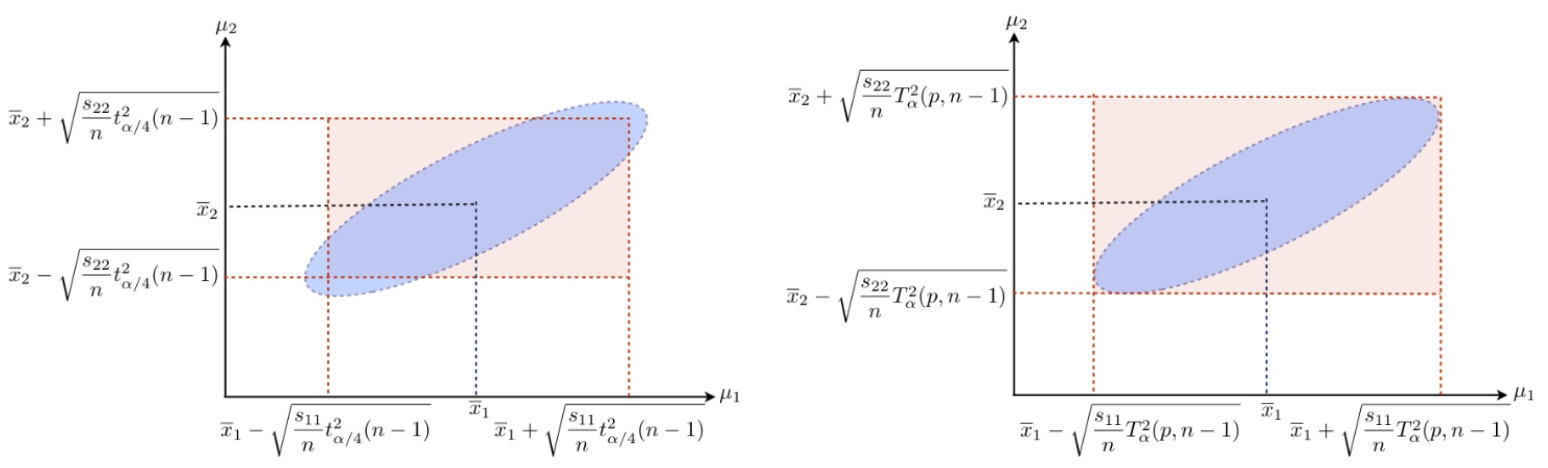

- Simultaneous confidence intervals for each component

Individual CIs: Sometimes people get used to confidence intervals for individual components, such as

\[ \bar{x}_{j}-t^{\alpha / 2}_{n-1} \frac{s_j}{\sqrt{n}} <\mu_{j}<\bar{x}_{j}+t^{\alpha / 2}_{n-1} \frac{s_j}{\sqrt{n}} \]where \(\bar{x}_j\) and \(s_j\) are respectively the sample mean and standard deviation of the \(j\)-th variate that has mean \(\mu_j\). But there are multiple testing issues. We can then use Bonferroni or Scheffe simultaneous C.I.s to correct this.

The \((1-\alpha)100\%\) Bonferroni simultaneous C.I.s for \(m\) pre-determined linear components of means, \(\boldsymbol{a}_{i}^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mu}(i=1, \ldots, m)\), are given by

\[ \boldsymbol{a}_{i}^{\top} \bar{\boldsymbol{x}} \pm t ^{\alpha/(2m)}_{n-1} \sqrt{\frac{\boldsymbol{a}_{i}^{\top} \boldsymbol{S} \boldsymbol{a}_{i}}{n}} \]

The \((1-\alpha)100\%\) Scheffe simultaneous C.I.s for all possible linear combinations of means \(\boldsymbol{a} ^{\top} \boldsymbol{\mu}\) are given by

\[ \boldsymbol{a}^{\top} \bar{\boldsymbol{x}} \pm \sqrt{T_{\alpha}^{2}(p, n-1)} \sqrt{\frac{\boldsymbol{a}^{\top} \boldsymbol{S a}}{n}} \]Pros: Compared with the advantages of ellipsoidal confidence regions, these hyper-rectangles (orthotopes) are easier to form and to compute.

Cons: Both Bonferroni and Scheffé intervals are wider (hence less accurate) than the ordinary confidence intervals which are constructed with separate confidence level of \((1-\alpha)\).

Fig. 29 Bonferroni (left) and Scheffe (right) simultaneous C.I.s.¶

If we just want to conduct univariate tests of means \(H_0: \mu_k = 0\) for each \(k = 1, 2, \ldots, p\), i.e. \(\boldsymbol{a} _k = \boldsymbol{e} _k\), then the C.I. has the general form \(\bar{x}_{k} \pm c_{n, p, \alpha} \sqrt{\frac{s_{k k}}{n}}\) for some multiplier \(c_{n, p, \alpha}\) depending on \(n,p,\alpha\). The above methods can be summarized as follows

marginal C.I. using \(t\) statistics (ignoring dependence among components): \(t_{n-1}^{\alpha/2}\)

Bonferroni simultaneous C.I. using \(t\) statistics: \(t_{n-1}^{\alpha/(2p)}\)

Scheffe simultaneous C.I.: \(\sqrt{T^2_\alpha (p, n-1)}\)

Asymptotic simultaneous C.I. using \(\chi ^2\) statistic as \(n\) is large: \(\sqrt{\chi ^2 _p (\alpha)}\)

Two-sample Means¶

Given two samples of \(p\)-variates, we are interest in whether their means are equal.

Paired¶

First, we consider paired comparison for two dependent samples.

This is easy, we just define \(\bar{\boldsymbol{d}} = \bar{\boldsymbol{x}}_1 - \bar{\boldsymbol{x}}_2\), and apply the above one-sample mean method to test \(H_0: \boldsymbol{d} = \boldsymbol{0}\).

More precisely, if \(\boldsymbol{d} \sim \mathcal{N} _p (\boldsymbol{\delta}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _d)\)

Two Independent Samples¶

We assume equal variance \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma} _1 = \boldsymbol{\Sigma} _2 = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\). The pooled sample covariance matrix is an unbiased estimator of it

By the independence between the two samples, the covariance of sample difference is

which can be estimated by \(\left(\frac{1}{n_{1}}+\frac{1}{n_{2}}\right) \boldsymbol{S}_{\text {pool }}\) since

Assume \(\boldsymbol{x} _1 \sim \mathcal{N} _p (\boldsymbol{\mu} _1, \boldsymbol{\Sigma} ), \boldsymbol{x} _2 \sim \mathcal{N} _p (\boldsymbol{\mu} _2, \boldsymbol{\Sigma} )\), then under \(H_0: \boldsymbol{\mu} _1 = \boldsymbol{\mu} _2\),

where

The \((1-\alpha)\%\) Bonferroni simultaneous confidence interval for the difference of the \(j\)-th component means \(\mu_{1j} - \mu_{2j}\) is

More generally,

\((1-\alpha)\%\) Bonferroni intervals for pre-determined \(\boldsymbol{a}_{i}^{\top}\left(\boldsymbol{\mu}_{1}-\boldsymbol{\mu}_{2}\right), i=1, \ldots, k\) is

\[ \boldsymbol{a}_{i}^{\top}\left(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}_{1}- \bar{\boldsymbol{x}}_{2}\right) \pm t_{n_{1}+n_{2}-2}^{\alpha / (2 k)} \sqrt{\left(\frac{1}{n_{1}}+\frac{1}{n_{2}}\right)\boldsymbol{a}_{i}^{\top} \boldsymbol{S}_{\text{pool} } \boldsymbol{a}_{i}} \]\((1-\alpha)\%\) Scheffe simultaneous intervals for \(\boldsymbol{a}^{\top}\left(\boldsymbol{\mu}_{1}-\boldsymbol{\mu}_{2}\right)\) for all \(\boldsymbol{a}\) is

\[ \boldsymbol{a}^{\top}\left(\bar{\boldsymbol{x}}_{1}- \bar{\boldsymbol{x}}_{2}\right) \pm \sqrt{T_{\alpha}^{2}\left(p, n_{1}+n_{2}-2\right)} \sqrt{\left(\frac{1}{n_{1}}+\frac{1}{n_{2}}\right)\boldsymbol{a}^{\top} \boldsymbol{S}_{\text{pool} } \boldsymbol{a}} \]

MANOVA¶

If there are multiple samples of multivariate observations, we use Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA). The data are treated as \(g\) sample groups of observed sample values, each sample group is from one of \(g\) populations.

Model¶

The MANOVA model, generalized from ANOVA, becomes

\(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) is the overall mean vector,

\(\boldsymbol{\tau} _{\ell}\) is the treatment effect vector of the \(\ell\) th population or treatment group,

\(\boldsymbol{e}_{\ell j} \sim N_{p}(0, \Sigma)\) is individual specific homogenous noise.

The parameter constraint here is \(\sum_{\ell=1}^{g} n_{\ell} \boldsymbol{\tau}_{\ell}=0\).

Analogous to the univariate case, the test of interest is

Equivalently, the model can be parameterized as \(\boldsymbol{x}_{\ell j} = \boldsymbol{\mu}_\ell + \boldsymbol{e}_{\ell j}\) without any parameter constraint, and the null hypothesis of equal treatment effects becomes equal means \(H_0: \boldsymbol{\mu} _1 = \ldots = \boldsymbol{\mu} _g\).

Test Statistic¶

The data can be decomposed similarly,

or

Then

Summing up, we have

since

The decomposition can be stated as

with corresponding degrees of freedom

Now we analyze the test statistic

Denote the between group (or between population) sum of squares and cross products matrix as

and the within group sum of squares and cross products matrix as

In fact \(\boldsymbol{W}\) is related to the pooled covariance matrix,

The MANOVA table is then

Since \(\boldsymbol{B}\) and \(\boldsymbol{W}\) are \(p \times p\) covariance matrices, the test statistic uses their determinants, or the generalized variances.

We introduce Wilks’ Lambda

which is the ratio of generalized variance of residual / generalized variance of total.

The distribution of \(\Lambda^{*}\) depends on \(p, g, n_\ell\) and is related to \(F\) distribution. When \(n = \sum n_\ell\) is large, Bartlett gives a simple chi-square approximation

Even for moderate sample size, it is good practice to check and compare both tests.

Note

We reject the null hypothesis that all group means are equal if the value of \(\Lambda^{*}\) is too “small”.

Wilks’ lambda is equivalent to the likelihood ratio test statistic.

Under the null Wilks’ lambda is of its own \(\Lambda^{*}\)-distribution, which is derived from the ratio of two random matrices \(\boldsymbol{W}\) and \(\boldsymbol{B} + \boldsymbol{W}\), each is of Wishart distribution

We can express Wilks’ lambda by eigenvalues of \(\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{W} ^{-1}\), which can be seen as signal-noise ratio. If it is large, then \(\lambda\) is large, and \(\Lambda^{*}\) is small.

\[ \Lambda^{*}=\frac{|\boldsymbol{W}|}{|\boldsymbol{B}+\boldsymbol{W}|}=\frac{1}{\left|\boldsymbol{W}^{-1} \boldsymbol{B}+\boldsymbol{I}\right|}=\prod_{k=1}^{p} \frac{1}{1+\lambda_{k}} \]The 2nd equality holds due to \(\operatorname{det}(\boldsymbol{X} \boldsymbol{Y} ) = \operatorname{det}(\boldsymbol{X} ) \operatorname{det} (\boldsymbol{Y})\). Note that since \((\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{W} ^{-1} )^{\top} = \boldsymbol{W} ^{-1} \boldsymbol{B}\), the two matrices \(\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{W} ^{-1}\) and \(\boldsymbol{W} ^{-1} \boldsymbol{B}\) share the same eigenvalues.

Other test statistics using the eigenvalues of \(\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{W} ^{-1}\) include

Hotelling-Lawley’s Trace: \(\operatorname{tr}\left(\mathbf{B W}^{-1}\right)=\sum_{k=1}^{p} \lambda_{k}\)

Pillai’s Trace: \(\operatorname{tr}\left(\boldsymbol{B}(\boldsymbol{B}+\boldsymbol{W})^{-1}\right)=\operatorname{tr}\left(\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{W}^{-1}\left(\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{W}^{-1}+\boldsymbol{I} \right)^{-1}\right)=\sum_{k=1}^{p} \frac{\lambda_{k}}{1+\lambda_{k}}\)

Roy’s Largest Root: \(\max _{k}\left\{\lambda_{k}\right\}=\left\|\boldsymbol{B} \boldsymbol{W}^{-1}\right\|_{\infty}\) which gives an upper bound.

C.I. for Difference in Two Means¶

If the null hypothesis of MANOVA is rejected, a natural question is, which treatments have significant effects?

To compare the effect of treatment \(k\) and treatment \(\ell\), the quantity of interests is the difference of the vectors \(\boldsymbol{\tau}_k - \boldsymbol{\tau}_\ell\) which is the same as \(\boldsymbol{\mu} _k - \boldsymbol{\mu} _\ell\). For two fixed \(k, \ell\), there are \(p\) variables to compare. For each variable \(i\), we want a confidence interval for \(\tau_{ki} - \tau_{\ell i}\), which have the form

where the multiplier \(c\) depends on the level and the type of the confidence interval.

Assuming mutual independence and equal variance \(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\) among the \(g\) samples, using Bonferroni correction, we have

\(c = t_{n-g}^{\alpha/2m}\), where \(m= p \binom{g}{2}\) is the number of simultaneous confidence intervals.

\(\widehat{\operatorname{Var}}\left(\hat{\tau}_{k i}-\hat{\tau}_{\ell i}\right)=\frac{w_{i i}}{n-g}\left(\frac{1}{n_{k}}+\frac{1}{n_{\ell}}\right)\) where \(w_{ii}\) is the diagonal entry of \(\boldsymbol{W}\).

Note that

The Bonferroni method often gives confidence intervals too wide to be practical even for moderate \(p\) and \(g\).

The equal variance can be tested.

Test for Equal Covariance¶

Are the variables in the \(g\) population groups sharing the same covariance structure?

Box’s \(M\)-test for equal covariance structure is a likelihood-ratio type of test. Denote

where

Box’s test is based on an approximation that the sampling distribution of \(\ln \Lambda\) is approximately of \(\chi ^2\) distribution under the equal covariance matrix hypothesis. Box’s \(M\) is defined as

Under the hypothesis \(H_0\) of equal covariance, approximately

where

\(u = \left(\sum_{\ell=1}^{g} \frac{1}{n_{\ell}-1}-\frac{1}{n-g}\right) \frac{2 p^{2}+3 p-1}{6(p+1)(g-1)}\)

\(v = p(p+1)(g-1)/2\)

\(H_0\) is rejected if \((1-u) M > \chi_{v}^{2}(\alpha)\). Box’s M-test works well for small \(p\) and \(g\) \((\le 5)\) and moderate to large \(n_\ell\) \((\ge 20)\).